Resource Library

From Collegiate Recovery Studies

A lot is happening in the world of addiction recovery. The growth and international dispersion of secular, spiritual, and religious recovery mutual aid organizations. The exponential growth of online recovery support resources. The emergence of resistance, resilience, and recovery as alternative organizing concepts for policy, planning, and funding bodies. Increased representation of people in recovery within addiction-focused policy and planning venues. Efforts to shift the design of addiction treatment from models of acute care to models of sustained recovery management nested within larger recovery-oriented systems of care. Expansion of peer recovery support services as adjuncts or alternatives to professional treatment. New recovery support institutions: recovery community organizations, recovery community centers, recovery residences, recovery support within educational settings, recovery industries, recovery ministries, recovery cafes, recovery music festivals, recovery adventure and sports venues. Large public recovery celebration events. Recovery-focused political lobbying. Expanded funding for recovery-focused research studies and an increase in the number of research scientists specializing in recovery research.

A lot is happening in the world of addiction recovery. The growth and international dispersion of secular, spiritual, and religious recovery mutual aid organizations. The exponential growth of online recovery support resources. The emergence of resistance, resilience, and recovery as alternative organizing concepts for policy, planning, and funding bodies. Increased representation of people in recovery within addiction-focused policy and planning venues. Efforts to shift the design of addiction treatment from models of acute care to models of sustained recovery management nested within larger recovery-oriented systems of care. Expansion of peer recovery support services as adjuncts or alternatives to professional treatment. New recovery support institutions: recovery community organizations, recovery community centers, recovery residences, recovery support within educational settings, recovery industries, recovery ministries, recovery cafes, recovery music festivals, recovery adventure and sports venues. Large public recovery celebration events. Recovery-focused political lobbying. Expanded funding for recovery-focused research studies and an increase in the number of research scientists specializing in recovery research.

These and related innovations are the downstream effects of the cultural and political mobilization of people in recovery and their allies. The emergence of a new recovery advocacy movement and an ecumenical culture of recovery reflects an important historical shift: people from diverse pathways of recovery identifying themselves as “a people” with a distinct history, shared needs, and a linked destiny. As this movement transitions beyond mass mobilization and institution building, it is pushing recovery-friendly policies and practices within law, government, health care, popular and social media, religion, business and industry, entertainment, and education.

Recovery-focused activities are evident in two arenas within institutions of higher education: the growth in collegiate recovery programs and recent calls for the creation of “recovery studies” on par with earlier academic specialties, e.g., Black/minority studies, women’s studies, disability studies, and queer studies.

Collegiate Recovery Programs

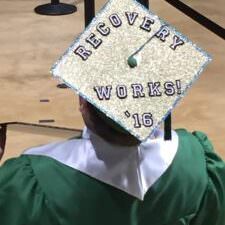

Collegiate Recovery Programs (CRPs) are structured supports for students in recovery on college campuses. The Collegiate Recovery Movement began at Brown University in 1977 and was later joined by programs at Rutgers, Texas Tech, and Augsburg. However, by the 2009 founding of the Association of Recovery in Higher Education (ARHE), there were still only a handful of such programs nationally. That has changed dramatically over the past 10 years as there are now more than 150 schools hosting a collegiate recovery program, spurred in part by a large grant program through Transforming Youth Recovery. These programs have evolved and diversified their scope of services: from the original schools whose programs were more formally structured and 12-Step focused, to programs that offer and support many pathways to recovery and provide a range of intensity and formalization of services.

While addiction-related stigma remains a problem among many University administrators and faculty, some schools have embraced CRPs as a part of larger equity and inclusion efforts. Students in recovery on campuses often report feeling marginalized and threatened by what are usually “abstinence-hostile environments”. The creation of recovery spaces, especially physical spaces with dedicated staff, offers students a retreat within the campus environment and serves to validate and support their identities as people in recovery. CRP Students are, on average, significantly older than other college students and thus are often managing additional challenges from being the oldest student in the class, to child care, part or full-time work, heavier familial responsibilities, and other obligations within their recovery community. CRPs seek to not only validate these students but to elevate and celebrate them as they balance school, work, and management of a chronic, and potentially fatal health condition.

Towards Recovery Competence as Cultural Competence

Efforts to grow recovery supports on college campuses are only a part of addressing a University’s responsibility towards people with severe substance use disorders and those in recovery. Far more people in recovery have and continue to navigate the rigors of higher education without CRPs. These students, like many staff and professors on college campuses, separate out their recovery identity from the relationship with the institution. This can create uncomfortable identity conflicts and also robs these institutions of the experience and wisdom that people in recovery have to offer. Creating spaces that encourage and nurture recovery identity enriches the experience of students, faculty, and staff across the university. It is also a moral and ethical imperative for schools that receive tens of millions of dollars in substance-related grant funding to provide recovery support for their own students, staff, and faculty.

Anecdotally speaking, people in recovery are well represented as students and professionals in fields such as substance use counseling, social work, psychology, rehabilitation, and mental health counseling. This is unsurprising given the academic trope “research is me-search”. In many of these classes and professions, students report their experiences being poorly represented or missing entirely in the literature, and worse are often discouraged explicitly or implicitly from sharing their recovery status in their programs or professions. Researchers in recovery frequently hide their recovery status to avoid being labeled as biased or for fear of reprisal within the tenure process. The irony and hypocrisy of the extensive stigma within both the academy and the field perpetuated by many in these “helping professions” demonstrate the necessity for explicit study and celebration of people in recovery through curricular inclusion and expectations of continual development of cultural competence around recovery for professionals.

Universities must learn from the tremendous contributions of Black Studies, Women’s Studies, LGBTQ and Disabilities studies departments who have not only greatly enhanced their own University’s dialogues around these issues but have provided the intellectual bedrock and framework of the most important movements towards equity and justice in our country. These programs have infused subject matter expertise and the voices of people within the communities into the content of teachings throughout the University, while also creating stand-alone fields. In the same way, the serious academic study and teaching of recovery on campuses across the country has the potential to greatly enhance the fields of Psychology, Social Work, Medicine, Counseling, Pharmacy, and Nursing and, in so doing, create a generation of professionals who have cultural competence in recovery, while also highlighting and celebrating recovery voices.

International Programme of Addiction Studies (IPAS)

The International Programme on Addiction Studies (IPAS) is a unique and distinguished academic study program that offers a global understanding of critical issues in the field of addiction. Primarily focused on prevention, treatment, policy, and research, IPAS brings together three of the world’s leading research universities, King’s College, London, the University of Adelaide, and Virginia Commonwealth University. Through distance learning, the Programme offers three graduate options to its students: a Master of Science in Addiction Studies, an Intermediate Graduate Certificate in International Addiction Studies, and an Advanced Graduate Certificate in International Addiction Studies.

Students learn to think critically about issues within the field of addiction science. Although recovery is not the primary focus of the program, students are taught to apply their critical knowledge of the field of addiction science to a variety of settings, including community-based settings addressing recovery supports and services, i.e., peer recovery support services, recovery community organizations, recovery community centers, recovery residences, and education-based recovery support services. The research project required to earn the Master of Science degree addresses key questions in addiction science and assists students in appraising the research literature and translating it into more effective policies and practices.

For many students, this course of study becomes part of the process to earn a PhD. For others it offers a more in depth opportunity to explore and analyze some of the discrepancies, gaps, and issues that exist in the addictions field. Individuals in long-term recovery have graduated from the program, most of whom are seeking to use their passion, lived experience, and knowledge of addiction science to prepare them for work in a variety of settings. One recent graduate has used the skills and knowledge received in the Programme to lead national recovery efforts on behalf of individuals and families in recovery.

More research is needed to advance the field of addiction, and to advance the understanding and field of addiction recovery. As more individuals develop an interest in addiction recovery, research programs like the International Programme on Addiction Studies will emphasize recovery as one of the focus areas of their programs. Until then, it is one of the only programs that requires exceptional students to extend their learning and focus their research projects on facets of recovery. These men and women are among the pioneers of the growing numbers of addiction recovery researchers and practitioners who are paving the way for the next generation and making huge strides in the understanding of and outcomes associated with addiction recovery in all of its phases, stages, and other expressions. Additionally, the multi-country, multi-site, and online nature of the collaboration creates opportunities to study and understand recovery in a variety of cultural contexts and pathways to recovery.

Recovery Studies

The addiction recovery field has undergone incredible growth over the past several decades. Even though many within the field have embraced a shift from pathology and clinical intervention to a focus on long-term personal and family recovery, many professionals still view and treat addiction as an acute condition.

With the lack of knowledge and expertise about recovery, there is a great need for qualified and trained addiction recovery professionals, including clinicians and researchers within the field. The need for these professionals will only increase over time as more and more people meet the criteria for severe substance use disorder and enter into recovery. Educational programs for mental health providers (e.g., social workers, counselors, marriage and family therapists, etc.) often do not have any classes dedicated to addiction let alone a focus on recovery. In addition to this lack of training, very few doctoral programs train researchers to study addiction and recovery. Thus, although more than 20 million people are in recovery in the United States, we do not know enough about how people enter recovery, navigate recovery, the multiple pathways of recovery (and what works for who), and how individuals and families stay in recovery over a life-time. The recent National Recovery Study indicated that on average it takes more than a decade of recovery for an individual to experience happiness and self-esteem on par with the rest of the population. We know too little about how to enhance the quality and durability of recovery.

Many bright and capable people have written and studied recovery in the past and their work provides a platform that is ripe for clinical improvement and scientific inquiry. Potential elements of recovery studies could include the following: history of addiction recovery, defining and measuring recovery, prevalence of recovery, neuroscience of recovery, multiple pathways of recovery (including harm reduction), stages of recovery, recovery durability (together with recurrence rates and risks), bio-psycho-social nature of addiction and recovery, behavioral addiction and recovery, and family and community recovery (within systems theory). In addition to these, we as professionals in the field need to understand the role and effectiveness of professional treatment and the power of recovery mutual aid organizations including extending recovery support through peer and community-based solutions (e.g., Collegiate Recovery Programs, Community Recovery Centers, etc.). Recovery studies should also include the relationship of recovery to prevention, early intervention, and the current issues and trends of the addiction recovery field.

For those who wish to be good consumers of recovery research or conduct that research, an understanding of the relevant literature and theories of recovery is necessary. Also, students of recovery must delve deeply into advanced research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, including advanced statistics. It is beyond time for the addiction recovery field to elevate ourselves to academic excellence and scientific rigor.

Texas Tech University’s (TTU) Department of Community, Family, and Addiction Sciences (CFAS) offers some insight into how educational programs can integrate recovery studies into their curriculum. In 1986, Texas Tech started a minor in Substance Abuse Studies (SAS), which attracted many students in recovery. These SAS students in recovery were taking classes to meet the educational requirements to become Licensed Chemical Dependency Counselors (LCDC) in the state of Texas. In 1988, Dr. Carl Anderson, a professor in the program and a person in long-term recovery himself, formed the Center for the Study of Addiction, which was one of the first collegiate recovery programs. The Center was later named the Center for the Study of Addiction and Recovery (CSAR 2003-2013) and is currently named the Center for Collegiate Recovery Communities (CCRC) (2013 – current). The name changes of the Center reflect the evolving understanding of addiction recovery and a transitional focus not only on recovery generally but on TTU’s collegiate recovery program specifically.

The SAS minor served and educated numerous students over many years. As the demand for more addiction recovery classes grew in 2007, the Community, Family, and Addiction Sciences (CFAS) department was formed and an undergraduate major in community, family, and addiction recovery was approved and implemented. The CFAS Department also offered programs in human services, addiction and recovery, and couple, marriage, and family therapy—with integrated classes on addiction and recovery. During the formation of the CFAS undergraduate degree, the former SAS minor was updated and underwent a name change to Addiction Disorders and Recovery Studies (ADRS).

Currently, the ADRS minor offers courses in understanding addiction and recovery, family dynamics of addiction and recovery, prevention, relationships, treatment, and research in addiction recovery. The minor continues to meet the educational requirements to become a LCDC in Texas. Presently the CFAS undergraduate major has 65 students and the ADRS minor has 302 students.

In July 2017, after many years of work, the CFAS department gained approval to start perhaps the first PhD. program focused solely on addiction recovery research. Grounded in Family Systems Theory, the ADRS PhD is a timely and unique program with the goal of creating scholars and academicians who have a passion for the science of addiction recovery. These doctoral scholars will have an understanding of addiction recovery, including relevant literature, recovery theories, and research methods and statistics. The students will be prepared to advance the field of addiction recovery with scientifically rigorous research studies from both the qualitative and quantitative traditions. The first cohort of PhD students started their work fall, 2019. Many within this first cohort of PhD students are persons in long-term recovery and products of collegiate recovery programs. With such a wonderful platform of recovery science built for us as a field, the future of addiction recovery knowledge, understanding, and research is bright.

Closing Reflection

Multiple factors set the stage for the expansion of collegiate recovery programs and the development of recovery studies programs at undergraduate and graduate levels. The former provide a dual emphasis on recovery support and academic excellence; the latter signal the recognition of addiction recovery as an important subject for critical academic inquiry. Historically, experiential knowledge and professional/scientific knowledge exist as two separate worlds within the alcohol and other drug problems arena. Collegiate recovery support programs and recovery studies curricula offer a potential bridge of integration between these two worlds. The future of recovery may rest within that integration.